It was a normal day of camp. The first day actually. Half a dozen third and forth graders were bent over a picture of my mother in her serious Twiggy years as a teenager.

Their task was to invent a character portrait for the woman in the photo, and they were doing a typical job of it.

Already they had decided:

- She had one neon green eye and one neon gray eye which both glowed in the dark as she slept in her red velvet bedroom.

- She was a professional murderer who invited people over to tea only to stab them when they were not looking.

- She ate chocolate covered crickets, blood crickets, and human finger cheese.

This is when things got weird. They also decided:

- She lived in a decrepit, old mansion haunted by a friendly ghost named Hari Cari and an evil, haunted doll named Annabelle.

That is when things changed, though we did not know it at first.

And in the intervening days, when Annabelle the Haunted Doll fever swept first through the children, then me, then eventually, my teaching assistant, we did not stop to think how strange all our lives had become. We did not muse over the fact that an idea — even an imaginary one, can be as real to us as something that actually lives in reality — circa the imagination.

Annabelle cropped up again that afternoon. The kids told me, as we were walking along the Greenbelt, that haunted dolls were “totally scary.”

“We saw an episode of The Haunting Hour with a haunted doll in it, and it was totally scary!” the kids said.

“Is the doll in the episode named Annabelle?”

“No,” the children said.

“Annabelle is the name of a bully at our school,” two girls chimed in. “That’s why we named her.”

It is the logic of children that you can punish a school bully by naming an evil, haunted doll in your summer writing camp after her, but the name stuck. Annabelle stuck.

The next day, when the kids opened up their binders to find my messy, cramped handwriting across their writing from the day before, they were delighted.

“Annabelle wrote us! She’s haunting us!” a girl shrieked with delight.

“Sorry,” I said, “it’s just me giving you constructive feedback.”

“Oh,” she said, disappointed. “Could Annabelle write us some notes too?” she asked.

“You want Annabelle to leave you notes in your binders,” I said, incredulously.

“Yes!” they all screamed in unison.

“What kind of notes? Nice? Scary?”

“Both!” they shrieked. “We want scary and nice!”

“Okay,” I said, “i’ll see what I can do.”

After the kids were picked up, I grabbed as many red markers as I could handle and left.

I went home and pulled out all their binders. What would a note written by an evil porcelain doll without movable fingers look like? I wondered completely unironically.

Annabelle was here I finally wrote in a half-Parkinson’s, half-REDRUM kind of handwriting.

It’s totally scary.

The next day, the kids immediately asked, “Did we get any notes from Annabelle?”

“I don’t know,” I said, hiding my smile. “What am I, her keeper?”

“Annabelle is so scary!” they said with delight when they saw the notes. “She’s so evil!”

One boy was less delighted.

“I don’t like Annabelle,” he said, his face crinkled up in anxiety and fear. “She is too scary.”

I went over to him.

“Annabelle will never haunt you again,” I said with certainty, as I tore the note from his binder, crinkling it up and throwing it into the trash for emphasis.

“How do you know that?” he asked.

“I just know. Annabelle will never bother you again,” I said, feeling like a boss in the mafia. “Fuggedaboutit!” I said.

“I’m Annabelle,” I finally whispered. “Shhhh,” I said, “it’s a secret.”

“Okay,” he said, his shoulders relaxing.

At the end of the day, the kids left a note on the whiteboard for Annabelle.

“You smell like farts,” the kids wrote. “Our revenge starts today,” they wrote.

“Give me a Ferrari,” one kid wrote.

“She’s not a genie,” I said. “She doesn’t grant wishes.”

“I know that,” he said. “I just want to see what she’ll write in response.”

“I do too,” I said, hiding my amusement.

By that point, I had decided that as evil and scary as Annabelle would be, she would also be polite. Like Hannibal Lector, she would be a civil, if evil, figure.

So, the next day, she wrote something very polite in response.

The kids were not fooled.

“Kill yourself,” one kid wrote back.

I neglected telling him that Annabelle the Haunted Doll could not die — because I didn’t want to get into an existential debate about whether animate objects had souls.

“That’s not nice,” I said. “What did Annabelle do to you?”

“You are a disgrace to doll-kind,” a kid wrote in response.

“At least that’s more constructive,” I said.

“At least that’s more constructive.”

But the kids were disappointed because there were no notes in their binders.

“Maybe she has touched the room in some other way,” I said when I saw their disappointment.

“What?” they said. “What do you mean?”

“Well, maybe she’s physically present in the room somehow, you know, in a corporeal way. Maybe she’s haunting us right now,” I added.

The kids scanned the room.

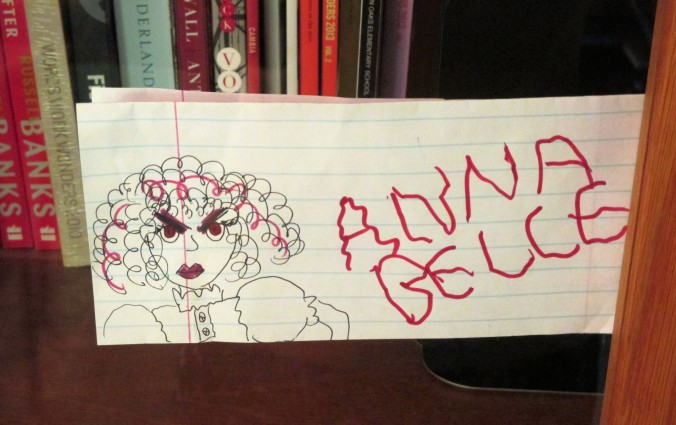

“I see her!” one shrieked. “She’s haunting the bookshelf!”

They crowded around to stare at her.

“Creepy!” they all agreed.

“I wonder if she is anywhere else?”

“What about that?” a kid said pointing to a patch of brown, stained plastic on the ceiling. “It looks like Annabelle had an accident.”

The kids started laughing. “She pooped her pants!” they screeched.

“Maybe” I said, neglecting to tell them that animate objects are not known for excretion — because I didn’t want to go into the semantics of biological digestive systems. Instead I said, “Where else do you see her? Look in the corners.”

“There’s Annabelle right there! She’s next to the whiteboard!” one kid said.

And she was.

“Look at her red, staring eyes,” they said.

“It’s like one of those paintings whose eyes follow you when you walk across the room. I’ll show you!” one kid said while walking in front of the drawing and demonstrating.

“Totally!” the other kids said in response.

“Totally!” I said, looking with amusement at my teaching assistant.

“Totally!” he said in response.

We went to the zoo. Inexplicably, there was a red shopping cart next to the entrance.

“Annabelle pushed it all the way here!” one kid said.

“Is Annabelle homeless?” I said under my breath.

“What?” the kids asked. “What about Annabelle?”

“Nothing,” I said, “it’s not important.”

I had not counted on the imaginative powers of children to makes things real, even the impossible, even though it’s why most people write. It’s why I write.

When we came out, the cart was gone.

“She hid it. She moved it again.” they said.

“Where?” I said. “Where did she move it to?”

“We don’t know,” they said. “She made it disappear.”

“Totally,” I said, neglecting to tell them about physics. “She must have.”

“Will Annabelle write us more notes in our binders tonight?” they asked.

“Okay,” I said, “okay.”

I wrote more notes. They all said I hope you are having a nice summer.

Very polite.

After camp, I went out and purchased some cheap, poseable dolls to lay around the classroom the next day.

By this time, all of this seemed normal. This was exactly how people are spending their lives right now, I thought. Exactly like this.

One of the doll heads was loose.

So I pulled it all the way off and then replaced it.

The next day, when the kids who wanted them had gotten their notes — (“She’s so scary!” one girl excitedly shrieked when she saw I hope you are having a nice summer scrawled across in the blood voice) — they pointed to the dolls Annabelle left for them in the center of the table.

“They’re not scary,” they said.

“They’re not, are they?” I said as I picked them up and accidentally twitched them so that the loose head flew off and across the classroom.

“AHHHH!” I screamed.

“AHHHH!” the kids screamed in response.

“Annabelle is crazy! She pulled its head off!” one kid said.

“I know! I can’t believe it!” another kid said in response.

“Can we take off the other doll head too?” one kid asked.

“Sure,” I said after pausing for a moment, “why not.”

As the kids worked on the final chapters of their stories, the dolls were passed from kid to kid, who twisted them into seemingly improbably shapes.

And constructed stories over shared head use.

“We can take turns wearing it!”

Or hid the heads entirely to become a tableau of lucid, inescapable rhythms played out in the classroom through doll heads.

I know noble accents / And lucid, inescapable rhythms . . .

But I know, too, / That the blackbird is involved / In what I know.

One kid began writing 10 words to describe Annabelle on the whiteboard. Other kids joined them. Then they filled the board with pictures of Annabelle and group epitaphs for themselves.

“Time to go,” I said. “Pack up your bags.”

The children packed while one boy and the teaching assistant played catch with one of the doll heads.

This is normal . . . this is normal child behavior I kept telling myself as I watched.

And then it was over.

“Should we tell them our secret? That you’re actually Annabelle?” the boy whispered to me as he caught the doll head.

“Okay,” I said, “you tell them.”

“Ladies and gentleman! We have an announcement! Hannah is actually Annabelle!” he shouted.

“No, really?” they asked, seemingly shocked. “Are you really?”

They had believed so much in Annabelle the last few days they forgot that they themselves had invented her. We forgot.

The magic of the imagination is that you can create a world that you yourself believe in. It’s powerful when it happens. So much so that I didn’t quite want to take it away from the children.

“I might be Annabelle,” I said, finally, “but I might not be Annabelle too,” I said, and winked.

“Annabelle needs to go on forever,” the kids told me. “Every camp this summer needs to be haunted by Annabelle,” they told me.

“Totally,” I said.

“Totally,” the kids said in response.

A week or so later, when it was all over, and the feeling of Annabelle fervor had cooled, everything seemed strangely out of joint in my mind. It had been like the eight of us had lived in a parallel universe for a week that no others could enter.

For a week, Annabelle had been like a secret handshake, but better. It was this world that we created and then believed in together.

And afterwards, the whole world we created seemed improbable, a shared experience that I could never quite explain to others.

“There was this haunted doll once, and it was amazing,” I said to friends.

“What?” they said. “A haunted what?”

“Never mind,” I said. “You’d just have to have been there.”